**● Scenari internazionali

**

Disclaimer: The author writes in a personal capacity. The views expressed in the article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the organizations to which the author is affiliated.

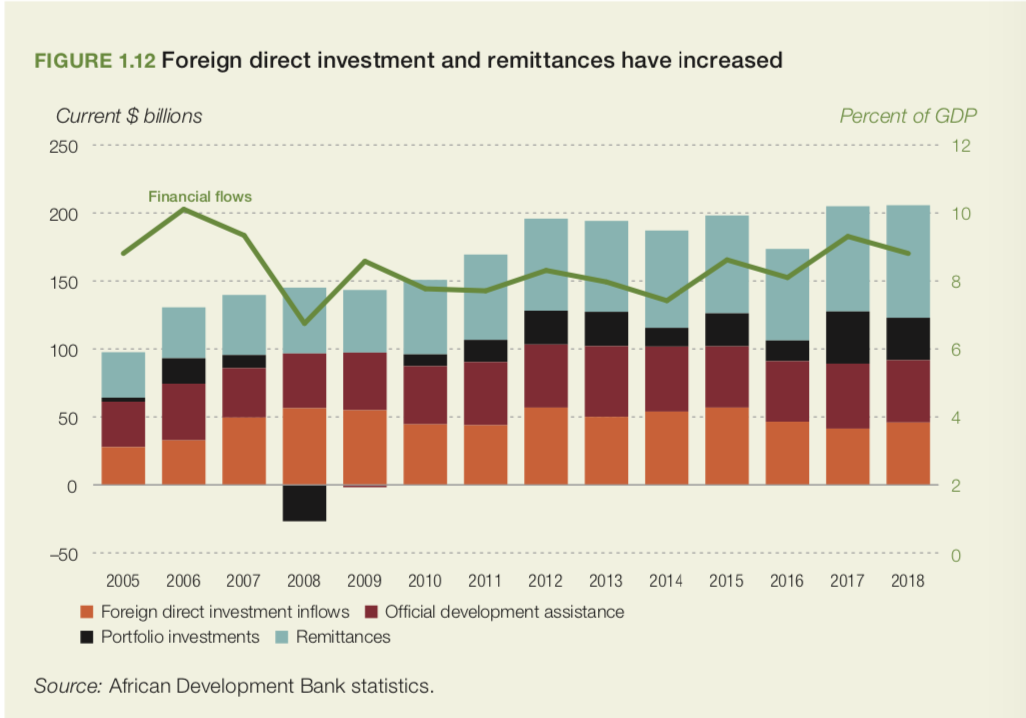

Coming to grips with the underwhelming projections of what to expect from African economies in the post-Covid-19 scenario cannot be easy for those in power. Few weeks ago, the G20 countries agreed to freeze debt payments for a year, freeing up $20 billion for the pandemic fight in poor countries. Still, African leaders have another (bigger) sword hanging. Due to Covid-19, the money migrants send home is set to decline dramatically. As remittances are a lifeline to millions and the highest source of external development finance, lowering transaction fees and speeding up transfer delays is now key to relaunching Africa’s development story.

On April 9, 2020, the World Bank released ‘Africa Pulse’, its biannual analysis of the near-term macroeconomic outlook for the region. The forecasts leave little room for imagination — African leaders need to bite the bullet: the pandemic could cost the region between $37 billion and $79 billion, marking the first regional recession in 25 years. The day after, on April 10, 2020, the African Union made an appeal to all governments. The press release can be broken down to three words: “Protect our migrants”. A statement from few days later explains why: “The majority of migrant workers are most exposed to the possibility of infection and risk of contagion.” Beyond health concerns, African leaders have another reason to be worried — and the debt freeze may not be enough to keep their tempers in check.

Why African leaders are worried

Figure 1: Remittances are the highest source of external development finance, US$ billions

**

Source:** African Development Bank. (2020: 26). African Economic Outlook.

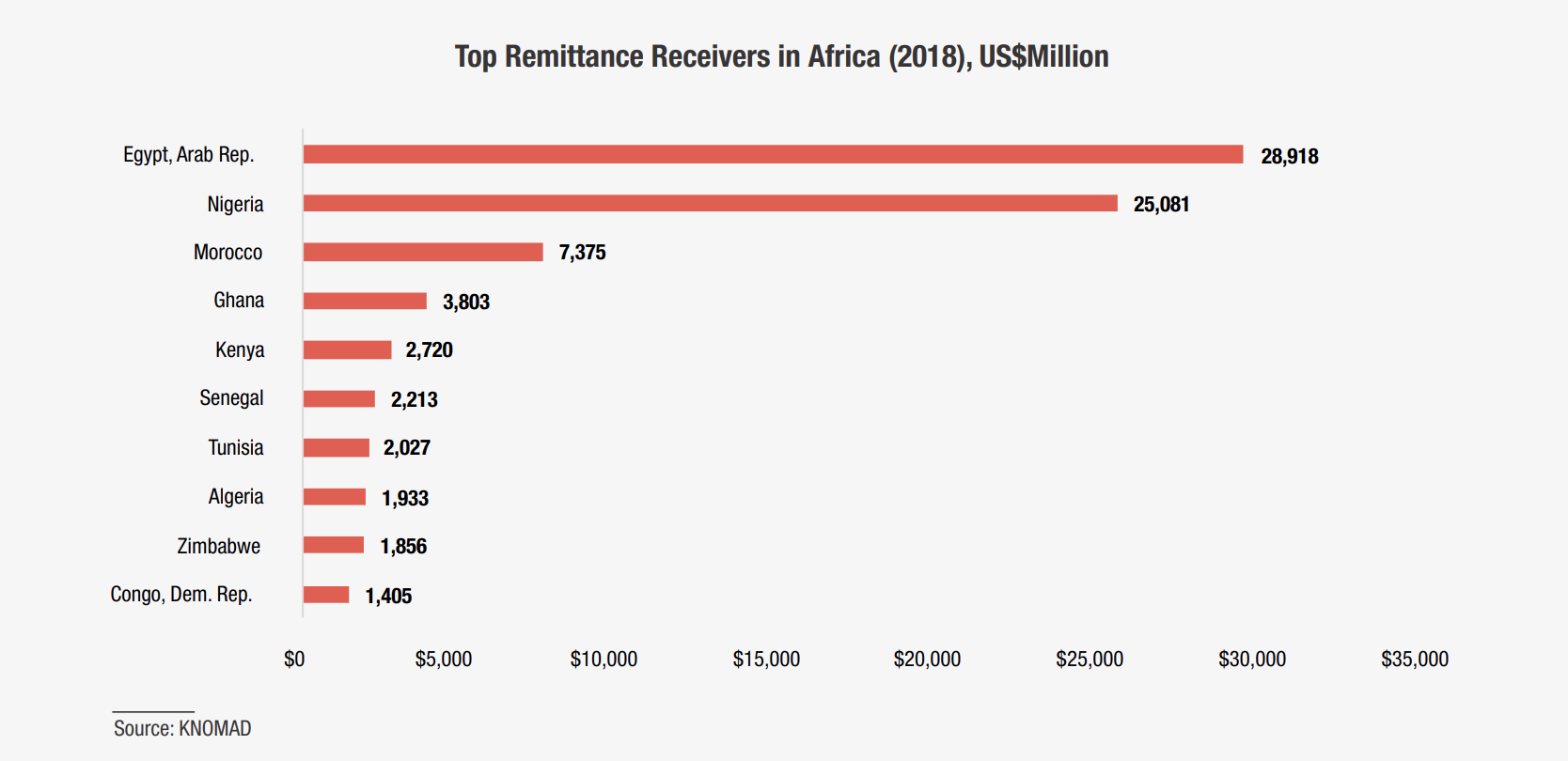

African workers abroad send (lots of) money home. Last year, migrant remittances to Africa hit a record high of $82.2 billion (of which $48 billion to Sub-Saharan Africa, the world’s poorest region), outperforming any other external financial inflow, including foreign direct investments and foreign aid. Remittances are not only a vital component of Africa’s economy, accounting for around 3.5% of the continent’s GDP (and for over 10% of the GDP of some of its poorest countries), but are also a key engine of Africa**’s growth.** The top remittance receivers are also the fastest-growing African economies (Ghana, Kenya and Senegal), plus Nigeria, Africa’s powerhouse, where migrant remittances have exceeded oil revenues for four consecutive years (PwC, 2019, p.4). Leveraging on the money migrants send home is central to trigger a self-made African development story. Not only are remittances over three times higher than foreign aid, but they also reach directly those who need them the most: millions of African households often depend on them for basic needs, such as food, housing bills and education.

Figure 2: Remittances across Sub-Saharan African countries, 2019 (% GDP)

Source: World Bank. (2020: 31). Africa Pulse.

Due to Covid-19, remittances sent to Sub Saharan Africa are set to decline by 23.1%, the greatest fall in recent history — from $48 billion in 2019 to $37 billion in 2020 (World Bank, 2020, p.33). According to the

International Monetary Fund, foreign workers have often been the first to see a dramatic decline in their incomes, being poorly targeted by policies put in place to respond to Covid-19. Less money earned means less money is being sent home. Worsening the economic chaos triggered by the pandemic in Africa, many families will go without food or shelter.

Beyond this projected fall, the families left behind are likely to be hit immediately by the closure of Money Transfer Operators such as Western Union and MoneyGram in the countries which have failed to consider them as essential services. Sure enough, the remittance lifeline has been suddenly cut for millions of African households. African leaders are worried. But what can be done about it?

There are at least two things that can be done: lowering transaction fees and promoting innovation in the remittance business. Regarding the former, while in 2015, all governments have pledged to cut remittance transaction fees to 3% by 2030 (as part of the Sustainable Development Goals), five years on, the price migrants pay for sending money home is still way higher. Money Transfer Operators dominate the industry and charge on average a 7% fee on each transaction (World Bank dataset, 2020). Based on a recorded volume of $529 billions of total remittances sent to developing countries in 2018, about $38 billion were lost in fees. This matters for two reasons. First, due to the Covid-19 crisis, there is an increased risk of severe food insecurity: the World Food Programme warned that acute hunger is set to double by the end of the year and an additional 130 million lives will be at risk. As remittances are often spent on food, lowering transaction costs can be a matter of life and death. Second, according to UNESCO, reducing global transaction costs to 3% from the current 7% could boost recipient families’ spending on education by $1 billion per year (UNESCO, 2019, p. 259). Such effect would be even greater in Africa, where transaction fees are the highest.

Lowering transaction fees

Transaction fees vary greatly. The global average cost of remitting (7%) does not allow us to take into account the stark differences existing between different channels and across countries. A report by the Overseas Development Institute shows that many corridors in Sub Saharan Africa carry fees of over 20% and up to 39%. On average, Africans living worldwide pay a fee of 9.3% on the money they send home (World Bank 2020, p.31). This means that sending home $200 equals paying around $220. In some cases, it can mean paying $240 or even $278: donating to loved ones in need is not for free and actually comes at a high price.

Meanwhile, in the G7 countries, not only does sending money home cost on average as little as 2% (sending $200 means paying $204), but also donations to developing countries can come at zero cost. In most advanced economies, the money donated to charities benefits from all sorts of fiscal advantages, ranging from pre-tax deductions to tax credits. According to the European Fundraising Association (2018, p.4), fourteen out of sixteen European countries offer tax incentives for individual donations to charities. For example, in France, individual donations to certain causes (including charities working with people in need) allows donors to benefit from a 75% tax reduction. This means that donating $200 to a charity helping (often unknown) women in Senegal can have an effective cost of around $50. Should charity have a price, statistics of European kindness may look very different (and potentially, underwhelming). In a similar way, should remittances have no cost, or should these flows even be encouraged and rewarded, statistics of African kindness in Covid-19 times may look very different (and potentially, overwhelming).

Promoting innovation: why fintech should be reading

Lower transaction fees will unlikely be put forth by those gaining (around $38 billion in revenue last year) from the market structure. The main winners of the remittance business are Money Transfer Operators which have sprung up like mushrooms in a rapidly growing market with a high potential (in the last ten years, remittances have grown by 65.5%). The remittance market is huge: an estimated $554 billion have been wired in 2019. This is approximately the size of six big markets combined[1]. Sure enough, the remittance market’s growth rates do not hide the elephant in the room: the market does not serve its customers, as users are not happy. Even more, they are frustrated. Not only transfer fees are disproportionately high, but transfers are slow (it can take days to send money home). In the midst of the Covid-19 outbreak, market inefficiencies are becoming increasingly unbearable for migrants.

As often the case, innovation disrupts dysfunctional markets before key players take innovation seriously. To prepare now for what’s next, fintech startups should join forces to innovate the market. Thanks to the speed of innovation and the reduced cost of hardware, a record number of developing countries are seeing an increase in smartphone and mobile phone ownership (European Commission, 2018, p.17). This, connected with poor banking infrastructure and concerns about the volatility of national currencies, has paved the way to blockchain-backed digital payments. Blockchain technology promises to revolutionize the remittance industry, speeding up processes via instant payments and lower transaction costs, even below the 3% target.

The use of digital technologies to innovate the remittance industry can go even beyond cheaper transactions. The extent to which African economies will be able to overcome the Covid-19 shock will depend on the development of solutions which do not only allow for instant and affordable transfers, but also frame remittances as something more than money transfers. The idea is that there is a transnational space where money is exchanged together with ideas, information, and concerns. The more fluid the communication flow between distant households, the more responsive the monetary flow. While traditional operators focus on money transfers only, a key issue undermining the potential of remittances to drive growth is information gaps between distant households – migrants cannot track the way their money is spent; mostly, they rely on hope their money is spent well.

Quite unsurprisingly, hope is not a viable growth strategy. As Adolfo Barajas, IMF, puts it, “Decades of remittances have contributed little to economic growth in receiving economies.” So far, ‘sending money home’ has meant sending money just to one’s family, often leading to private wealth (modern homes) and public squalor (unpaved streets). Unlocking all potentials of remittances means ensuring that these flows are channeled towards promising community projects, making money and communication flow together within communities beyond borders. To unlock the transformative potential of hundreds of billions a year, coupling money transfers with community-wide information exchanges is paramount. Social networks facilitating digital payments can free up more funds than the G20 countries combined. Indeed, if fintech startups are reading, African leaders can be less worried.

Immagine: Economy Barclays Remittance Money Transfer (23 ottobre 2013). Crediti: AMISOM Public Information, Creative Commons 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

[1] Gold ($170bn), iron ($115bn), copper ($91bn), aluminum ($90bn), zinc ($34bn), manganese ($30bn) and silver ($20bn). Source: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/size-oil-market/.

© Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana - Riproduzione riservata